Our new MSc student Prachi Chitre has written an excellent piece on the politics of culture, and culture of politics. Read here:

Shakespearean politics and the politics of Shakespeare

Hath not a Jew eyes? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you poison us, do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge?

(Shakespeare, 2005, 5.3:45)

It’s no secret that the Bard was the master of political intrigue. Some of his most famous plays – Julius Caesar, Antony and Cleopatra, Merchant of Venice, and The Tempest – all contain varying currents of historical politics at the time. Several critics have expounded heavily on how Shakespeare aptly captured and depicted a range of human characters, personalities and emotions, but perhaps more importantly how relevant these depictions are in today’s times too.

Shakespeare in India (The Hindu)

In India in 2018 there was a project started by schools across the country called Native Shakespeare, which encouraged the reading of various Shakespearean texts in native languages such as Hindi, Marathi, Gujarati and Kannada. The purpose behind this was to celebrate two unique cultures – an English tradition, reinterpreted by local peoples in their native languages. The project was an enormous success. At the time, I was working as an educator with a local school in my city for special needs children.

As one of the curriculum directors for the school, I engaged with the Maharashtrian Institute for Sign Language in order to adapt the play The Tempest for the school children. This involved developing a special curriculum and building apps which would convert the original text into Marathi and enable students to adapt and perform the play. The launch of this project had mixed reactions. From the cultural elite, it was a positive initiative to educate young minds and teach children about some of the finest literature that was ever written. On the other hand, certain media outlets viewed this as another form of colonialism. Why bring Shakespeare into the curriculum at all? Didn’t India have its own brilliant writers such as Tagore, Narayan, Seth and Desai?

At its very core, The Tempest – other than being a fantastical drama filled with magic, fairies and illusions -- is also deeply political. It talks about a ruler who was usurped, banished and who conquers a native island. It is also a story about reclamation and vengeance. Prospero’s role as ultimate dictator and authoritarian ruler, his control over Ariel, Caliban and his own daughter Miranda, raise pertinent questions of tyranny and rule. Who is a good leader? What are the qualities that draw a fine line between a hero and a despot? And most importantly, is anyone justified in any sort of conquest? Although written almost 500 years ago, Shakespeare’s last play has resounding echoes in today’s political climate. India, as the world’s largest democracy, is forced to encounter her own conundrum of tyranny, law, order and conquest. Almost seventy years after independence, she is struggling with the crushing weight of religious persecution, division and an inherent fear of diversity, differences and freedom of thought. Sectarianism tears the country apart. As an immigrant I must reckon Indians to ask themselves the same questions which Prospero asks in the Tempest: Are we really a brave new world? (Shakespeare, 2005, 5.5:20)

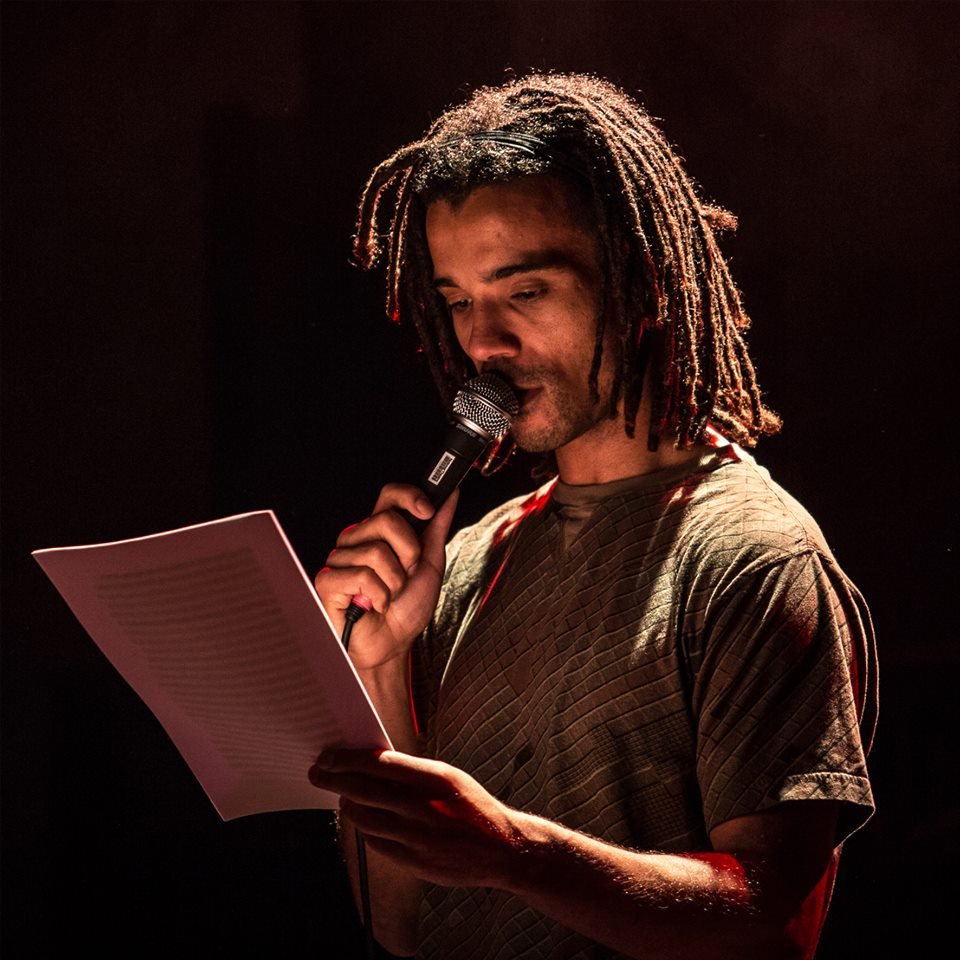

In 2011, a hip-hop artist Akala set in motion a project that explored global cultural debates about the power of language and its interpretations across the world. Akala, an award winning hip-hop artist, collaborated with the British Council in order to promote the arts across multiple countries including Australia, New Zealand, Vietnam and Africa. He launched the Hip-hop Shakespeare Company, a music production house and invited famous actors such as Sir Ian McKellen and Cicely Berry to participate. Merchant of Venice was one of his special productions that incorporated hip-hop into the script, adapting the play for a 21st century audience. This was a unique initiative to reach out to millennials and the Gen-Z population who commonly regard Shakespeare as archaic and out of date. But Akala managed to appeal to the sensibility of the younger generations by speaking their language and passing on the timeless essence of fine literature and art. (TedX x 2011)

Akala x Shakespeare (Google Images)

Merchant of Venice addresses religious persecution. But it also talks about persecution in general: the rich versus the poor, the privileged versus the unprivileged, the first world versus the third world. In the 21st century, we are not any far from persecution than audiences in the 16th century knew. At the time of writing this article, the war against Ukraine is very much being waged, another war in Israel-Palestine has recently erupted, not to mention the innumerable conflicts and examples of civil violence happening in the Middle East, Africa, and across Europe. Although historical contexts and timelines might vary, the narrative is always the same: it is the weaker sections of society being persecuted by the supposedly stronger, dominating ones. America in particular seems to encounter persecution on a new level of intolerance and polarisation: gun control, abortion rights, and anti-immigrant spirit all point towards a breakdown in democratic systems and a decline in inclusive spirit.

Last, but not the least, perhaps my favourite Shakespearean drama would have to be Julius Caesar. In this play, probably Shakespeare’s most masterfully-packed political tragedy, readers encounter a real-historical event that was brought to life by the playwright. The fluidity and impact of language, the quick shift of scenes and the thunderous speeches by Brutus and Antony continue to win hearts even today. Last year, I had the opportunity to witness an adaptation of Julius Caesar at the National Theatre in London. It was a unique, post-modern version in which Caesar was a successful finance tycoon. It also had fun features such as mapping the Tube’s arrival onto Caesar’s death: ‘One minute until Julius Caesar dies,’ building a momentum which was volcanic. (Julius Caesar, 2022)

Julius Caesar, London (Archives, Royal National Theatre)

What was interesting about the postmodern version was that the themes of murder, betrayal, succession and political turmoil are as in tune with a 21st century world as they were with 16th century Elizabethan England. One could hardly misplace the new Julius Caesar at Wall Street as compared to the original Roman general. This play was also interactive. The audience were encouraged to complete online surveys during performances, the results of which were displayed on a screen. The data from all these surveys was then compiled and fed into an Instagram series called: Et tu Brute? It aimed to understand how modern audiences feel about large-scale political betrayal, assassination, drama and the continuation of dominant empires (no different than Rome in 44 BC).

The survey asked some thought-provoking questions: Do the means always justify the ends? Do we answer first to the call of duty or to personal convictions? What separates the personal from the political? How do we deify our leaders and then justify their downfall? As we loom towards a new technological, political and economic dawn in the history of mankind, do we really follow Brutus’ advice, ‘there’s a tide in the affairs of men, when taken at the flood leads on to fortune’ (Shakespeare, 2005, 1.2:177) or like Cassius, do we reluctantly admit that ‘The fault is not in our stars, but in ourselves?’ (Shakespeare, 2005, 1.2:155)

References

Acharya, S. (2019). ‘Should Shakespeare Still be Taught in Indian Schools?’, The Curious Reader, (April), pp.8-15

Dickinson, A. (2016). ‘Global Shakespeare’, British Library, 17(3), pp. 257-268. doi: https://www.bl.uk/shakespeare/articles/global-shakespeare

Julius Caesar. William Shakespeare. (2022). Directed by David Smith. [National Theatre, London. 14 November].

Shakespeare, W. (2005). Merchant of Venice. Edited by Stephen Greenblatt. London: Penguin. 5.3:45.

Shakespeare, W. (2005). The Tempest. Edited by Stephen Greenblatt. London: Penguin. 5.5:20.

Shakespeare, W. (2005). Julius Caesar. Edited by Stephen Greenblatt. London: Penguin. 1.2:177.

Shakespeare, W. (2005). Julius Caesar. Edited by Stephen Greenblatt. London: Penguin. 1.2:155.

TedXTalks (2011) Hip-Hop & Shakespeare? Akala at TEDXAldeburgh. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DSbtkLA3GrY