(Images originally from MBC On Focus, 28 May; reproduced here)

When I was doing my MA a few years back, a tutor mentioned one day that Korean pro-democracy student activists looked like well-trained soldiers when they threw Molotov cocktails. I don't remember why the topic was brought up in the first place but I remember being quite surprised at learning the existence of such a reputation outside the country. After the mid-1990s, however, street protests of such kind seem to have become a thing of the past. Or at least replaced by a more pacific version. Since 2002, when there was a series of commemorations for the two teenage girls killed in a vehicle accident caused by two American soldiers, protests have invariably taken the form of candlelight vigils in Jongro Square, Central Seoul. And it was the case with the one against the beef import deal, too. Until last weekend. After 16 times of candlelight rallies in vain, frustrated protesters eventually stayed gathered until early in the morning [* according to the Korean law, you need a pre-granted permission to protest and you can't protest after the sun sets] and some of them started to march on the roadway until they all were taken to the police station. The police also announced that they intend to arrest anyone who violates the law on public assembly and demonstrations. In this context, the biggest issue in Korean cyberspace at the moment is whether the authorities' hard-handed reaction is justifiable. What makes the citizen protesters angrier is not the embedded violation of human rights by the current legal framework in general. The reason is rather that the rallies are NOT "ideologically motivated" like the authorities and the pro-government media define. I am by no means saying that it's okay to be hard-handed via-à-vis ideologically motivated activism, but the point to be made here is the mass of protesters this time, which the authorities said they would take any necessary measures to stop, is indeed composed of those who wouldn't usually be engaged in collective action like this: mums that brought their children with them, teenagers after school, young ladies in their high heels, etc. Therefore, those who have been participating in the rallies and those who sympathise with the protesters flood online discussion forums and comment boxes on news portals with the question, "Hundreds of riot police with their shields? Are we really in 2008 or in the 1980s?" On the other hand, the authorities' argument is that that what's illegal is illegal, it was the citizen protesters that turned violent first, and the police only reacted to that.

It shouldn't be my place to say which account is what exactly happened because I wasn't there, but what I dread to notice is the striking similarity between what the authorities of today say and what the military government in the 1980s said when they sent paratroopers to major cities to quell pro-democracy protests. The Gwangju Massacre in May 1980 had been officially regarded as a rebellion inspired by communist sympathisers, and it took almost a decade before it received recognition as an effort to restore democracy from military rule. The police appeal that it is not fair to compare what's happening now with what happened in the 1980s, given how things have changed. I know there has been no gun, no tear gas, etc. I don't think, however, that the comparison is meant to be a simple equating anyway. It's more about the fear of "going backwards in democracy". Can we blame someone for being shy after bitten once?

Hence, while rallying, today's protesters in Korea also live-broadcast their rallies through their mobile phones, webcams and laptops. This is not just to mobilise more people but, perhaps more importantly, to protect themselves from potential government propaganda and media distortion against them. In other words, they are making sure that the rest at their homes see that there are no pro-communists behind the protests and that no violence is initiated by the protesters.

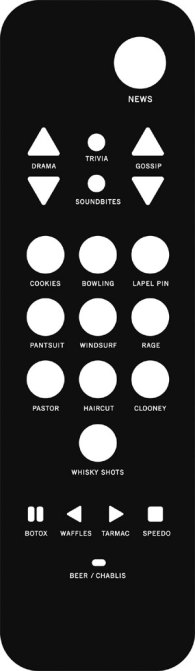

Liberal news media like Hankyoreh, OhmyNews and MBC (above) put welcoming spotlight on this phenomenon, commenting that this is a new version of digital journalism. Sounds cool and cutting edge, but saddens me personally. One of my interviewees, who happened to have been directly exposed to the 'Gwangju Uprising', told me that he was really shocked when he moved to Seoul immediately after the incident and found that people in Seoul had no idea what'd happened in Gwangju and vaguely guessed that it was a rebellion orchestrated by pro-communists, just like the government and the pro-government media said. He added that he regretted that things would have been different if there had been for the Internet. The first model of DIY journalism, OhmyNews, was born in Korea and now a version two. What's going on is unfortunate enough, but I also find it sad that the impressive level of technological sophistication that Korean civil society is often associated with in the literature seems acquired out of necessity.