Only hours to go until the American presidential election kicks of for real in Iowa. Anyone else excited?

Of course, it should be noted that Iowa is a notoriously unpredictable place. This is because the event being run isn't a primary (New Hampshire has the honour of holding the first one of those) but a caucus. This is a very different form of democracy - very old-fashioned, very participatory. This also reduces the turnout. Indeed, this event - which is being covered by thousands of news people from all over the world, and has cost millions and millions of dollars - will likely only have (at the absolute most) a couple of hundred thousand people involved in it.

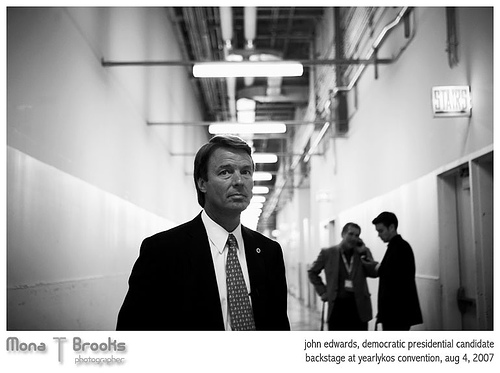

This also makes polling very, very difficult. In 2004, the Des Moines Register got a lot of kudos because it got things pretty much right in the run up to the contest - notably picking up the late rise of John Edwards through the field. Furthermore, a recent poll organised by opinion polling blogger Mark Blumenthal found that the Des Moines Register poll, undertaken by Selzer, was the most reliable in the field. A couple of days, then, the Register published its much anticipated last pre-Iowa poll. And the results were as follows:

Barack Obama - 32

Hillary Clinton - 25

John Edwards - 24

Mike Huckabee - 32

Mitt Romney - 26

John McCain - 13

The Democratic side of the poll has proved particularly controversial, with both the Clinton and Edwards campaign issuing immediate press releases rebutting some of the findings of the poll (for example, Clinton's pollster, Mark Penn). In particular, Obama's majority in the Selzer poll is largely constructed from a very high number of independents and even Republicans who said they were willing to come out and vote for him. And when I say high, I mean high - 45 per cent of the total predicted turnout. So, the argument goes, these numbers are flawed because, when push-comes-to-shove and its snowing in Iowa, these people won't turnout. We have to be careful here, there is a lot of spin doing the rounds, but the criticism does seem to make some sense. In 2004, for example, independents and GOP voters only constituted 19 per cent of caucus goers. At the very least, if Obama wins the caucus in the way that the Register poll suggest, it will be nothing short of a seismic event in American politics.

It is the question of turnout - and the unpredictability of it in a caucus environment - that perhaps does most to explain the extreme variance across the polls. At the same time as the Register poll came out, CNN were publishing another poll, which showed this:

Hillary Clinton - 33

Barack Obama - 31

John Edwards - 22

Mitt Romney - 31

Mike Huckabee - 28

Fred Thompson - 13

John McCain - 10

So what's the alternative? In a ridiculously ambitious (and, as it turned out, moderately time consuming) experiment I thought I would it would be fun to take the pollsters on with a different method - by harnessing the wisdom of crowds. I was flicking around the web, when I noticed that the Washington Post Fix blog had published a "predict the result" column. This was racking up dozens of predictions. So I copied and pasted them into an excel spreadsheet and then calculated the averages (the last comment I sampled was hal24, posted at 3:24 pm). Actually, the Fix column also has expert predictions on it, so this is in fact a test of three methods - pollsters, expert picks and the crowd. Here's the collective outcome of Fix commentators:

Barack Obama - 31.6

Hillary Clinton - 28.7

John Edwards - 27.9

[n = 75]

Mitt Romney - 29.9

Mike Huckabee - 29.5

John McCain - 18.5

[n = 69]

(Here is the spreadsheet with the workings, plus a proper comparison with the media polls).

The crowd results lead to a number of conclusions:

- Barack Obama will win for the Democrats, with a solid margin over Hillary Clinton.

- Mitt Romney will see off Huckabee in a very tight race.

- Edwards will do considerably better than the pollsters predict.

- John McCain will do considerably better than the pollsters predict.

It is these last two predictions that are perhaps most interesting, as that is where we see the greatest divergence between pollsters and the predictions of the Fix's readers, especially in the case of John McCain.

There are plenty of reasons to doubt the ability of the crowd - they might be multiple posting, many of them will have candidate preferences, their views might be warped by who can post at any given time - but it is still an interesting experiment. We'll have to wait until tomorrow morning to find out exactly who got it right though.

OK, so the results are in... and didn't the crowd do well! Here's the list, comparing them with the other predictions we had available. I did some quick (and probably horribly unscientific) calculations to assess who was closest. Basically, I took the prediction for all six candidates away from the actual percentage they got, then added them together and divided them by six to get an average predictive difference (you can see the workings here).

The crowd were only beaten by two of the experts and the Register poll. They managed to beat six experts and one multinational news organisations opinion poll. Not bad. Furthermore, the average of the crowd was also better than the average from the experts, which was 4.63, meaning the crowd was 0.75 more accurate.