Akil Awan writes for The National Interest on the Paris terrorist attacks, comparing them to the Anarchist wave of terrorism that plagued Europe and the US, over 120 years ago. He uncovers the uncanny parallels between the two, reflecting on the increasingly polarised political discourse in both eras that resulted in knee-jerk, draconian security and state responses, as well as rampant anti-immigrant rhetoric and legislation. He encourages policymakers to reflect on history and warns against repeating the mistakes made in delaing with the anarchist scourge.

The National Interest, November 21, 2015

Akil N Awan

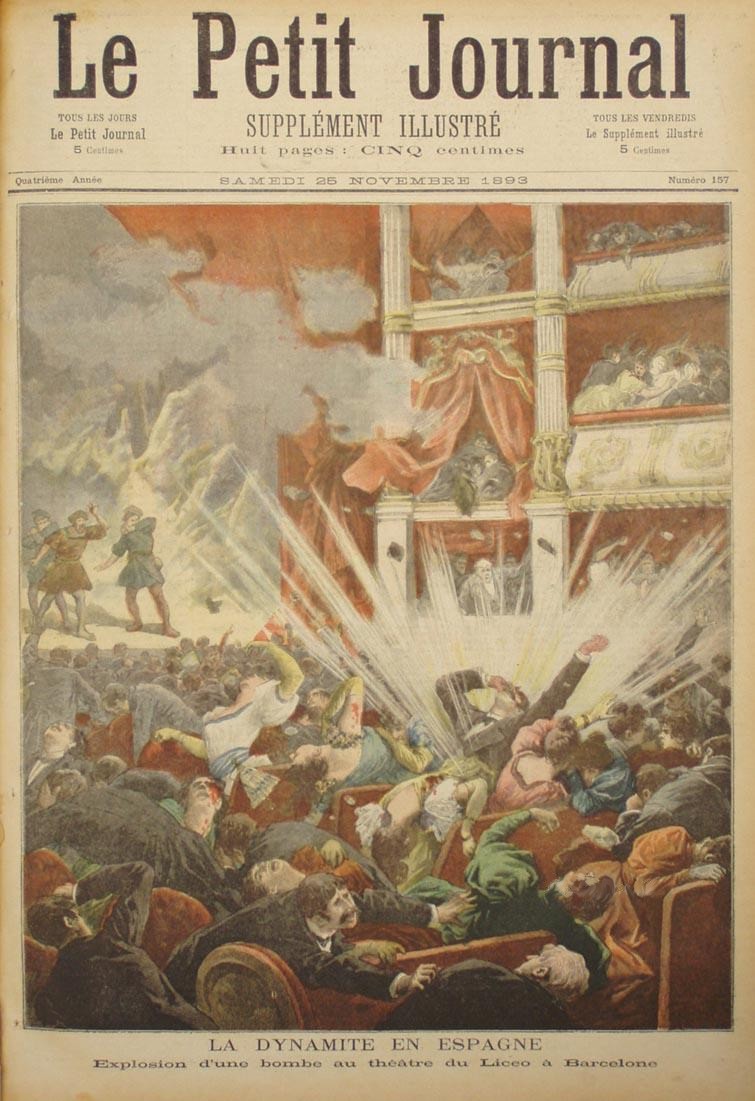

The bearded young terrorist furtively slipped amongst the oblivious theatergoers. Glancing around to ensure he had not aroused suspicion, he looked out over the crowded throngs in the theater. Blissfully unaware of the carnage that awaited them, they laughed and reveled in their petty entertainments, he mused, while his own people suffered and died. They would all pay, he consoled himself, as he hurled the bombs into their midst. The unspeakable horror that ensued, of shattered lives and limbs, was quickly emblazoned on the front page of French newspapers. Elsewhere, a second terrorist walked into a small trendy café in Paris. Scanning the oblivious faces—ordinary French men and women—as they sat drinking and listening to music, he placed his bomb under a table. As he slipped away, he heard the bomb explode, followed by a deafening silence, only to be punctuated by the terrible wails and screams of the survivors. There are no innocents, and they all deserve to die, he rehearsed in his mind, drowning out the cries of the victims behind him.

These events did not occur in Paris last week. Eerily, they took place over 120 years ago in European capitals as the scourge of anarchist terrorism was sweeping the continent. Santiago Salvador had attacked the Liceu Opera House in Barcelona in 1893, during a packed performance of the operaWilliam Tell, killing twenty-two people and injuring thirty-five. A few months later, Emile Henry had set off a bomb in the Café Terminus in Paris, killing one and wounding twenty, but had hoped for a far higher death toll. Images capturing the shocking events made the covers of the world’s largest daily newspapers of the time, Le Petit Journal and Le Petit Parisien. Both had a combined daily circulation of around seven million copies, depressingly illustrating how terrorism has long wielded the power to transform local tragedies to European catastrophes. In their subsequent trials, the anarchist terrorists showed no remorse for their terrible crimes, refusing to accept that ordinary bourgeois theatergoers or coffee drinkers could be considered innocent. Instead, they went to the guillotine, defiantly reeling off a litany of the crimes committed by the state and wider society.

These angry young radicals used bombs and guns to terrorize their own societies in furtherance of a foreign creed, in much the same way that jihadists recently did in Paris. The similarities are truly uncanny. If there is one salient difference, it is that the anarchists were actually far more successful in their campaign than the jihadists today. In a short period of time, they managed to assassinate an impressive list of world leaders, including two U.S. presidents, the Russian tsar, the German Kaiser, the French and Italian presidents, the Italian king, the Austria-Hungarian empress and two prime ministers of Spain, as well as a whole host of the European ruling classes. They also targeted the bourgeois masses indiscriminately, increasingly failing to distinguish between the state and wider society, attacking targets as disparate as the Paris Stock Exchange, religious processions in Barcelona, the London Underground and the Greenwich Observatory. The London Times newspaper wrote at the time of an “anarchist epidemic.”

The response to anarchist terror was unnervingly similar to our own experience too. The state clamped down in typically repressive fashion, instituting a range of iniquitous laws and meting out extrajudicial, and often collective, punishment to large swathes of society. The assassination of U.S. President William McKinley in 1901, for example, by an anarchist who also happened to be a second-generation Polish immigrant, led to the expedited introduction of anti-immigration legislation which required the exclusion and deportation of anyone suspected of anarchist sympathies. Anti-anarchist propaganda images from the period are disquietingly reminiscent of the increasingly hardened attitudes we are already witnessing towards Syrian refugees. One typical U.S. political cartoon shows a swarthy, bearded, foreign anarchist, armed with a knife and bomb, creeping up behind the statue of Liberty, who holds her beacon aloft and calls out naively, “come unto me, ye opprest!”

In the European mainland, wide-scale surveillance of meetings and publications was followed by arrests and torture, and used to draw forced confessions. Indeed, various Western governments used the ominous threat of anarchist terror to then subdue any form of dissent against the state.

All of this had little tangible effect on the anarchists themselves. In fact, the anarchists executed by the state were often transformed into martyrs. The apathetic masses, who up until this point had remained largely indifferent to the anarchists’ propaganda, were increasingly polarized by the state’s draconian response. Indeed, the harder the state clamped down, the more powerful the movement became. The fear and insecurity engendered within this environment also granted tremendous powers to the state, which it could then use and abuse, to the detriment of society at large.

Why should this concern us? Most people have probably never heard of the anarchist reign of terror at all. However, that in itself is an important observation to make. Despite the spectacular violent successes of anarchist terrorism at the time—far more so than those of the jihadists today—anarchism achieved very little in the sociopolitical sphere in the long run. Within four decades, the violent ideology had consumed itself and in the process alienated any potential support base, quickly being replaced by more popular movements. The anarchists were soon forgotten and ultimately consigned to the wastebin of history. However, the anarchists do offer us two crucial lessons for dealing with the jihadist threat today.

Continue reading here